The Plasmon Saga. Notebook 2025-9.

By Ian Cressman

Plasmon is a powder, milk albumen, which could be mixed into various other foods to make it palatable.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Industrial Revolution changed the nature of food production worldwide. As the advent of efficient farm tools and larger factories enabled more production of manufactured food, prices dropped, and many Americans found that they could access food more easily. But as the amount of food in households increased, society also found itself facing a new problem: food waste. Thus, the late 1800s and early 1900s also marked a period of scientific inquiry into strategies to diminish food waste. And by the end of the 19th century, while researching ways to reduce food waste, a Swiss (some sources say German) chemist called Seibold (some sources say Siebold) developed what he believed to be the world’s newfound superfood. Using skimmed milk waste and containing incredible nutritional value, Seibold’s discovery would eventually become known as “Plasmon.” 1.

Recognizing the potential value of his invention, Seibold sold the license for his product to a group of investors in London, who helped form the Plasmon International Company. Plasmon quickly developed a strong following from those involved in the Physical Culture movement, which promoted health and strength training, and first sprouted during the mid-1800s. Among Plasmon's biggest supporters were Eugene Sandow (a man often considered the father of modern bodybuilding), who appreciated the product’s high protein content, and Eustace Miles, an English tennis player who saw plasmon as a nutritional powerhouse for the vegetarian world. Many of plasmon’s claims are now recognized as pseudoscience, but back then, its ties to strength and masculinity became so popular that Sandow claimed, “Plasmon is the essential food I have so long wished for, and I would never be without it.” Plasmon biscuits were even used by Ernest Shackleton for a Christmas lunch during his 1902 Antarctic expedition. He wrote: "Had a hot lunch. I was cook: – Bovril, chocolate and plasmon biscuit, two Spoonfuls of jam each. Grand!" 2, 3.

But Plasmon also has a surprising connection to Briarcliff Manor, and specifically to a man named William Woodward Baldwin. A graduate of Maryland Law, Baldwin opened his own law practice in New York City in 1888 and later moved with his family to Briarcliff Manor in the autumn of 1897. Upon his arrival in Briarcliff Manor, Baldwin met the founder of the Village of Briarcliff Manor, Walter William Law and found him an “agreeable little Scotsman with a fascinating smile and bright blue eyes.” 5. Law took Baldwin to lunch at the Mt. Pleasant Field Club, and as Baldwin came to know him, he was suitably impressed by Law’s achievements and Briarcliff Manor itself.

Baldwin and Law remained quite close for decades, and Baldwin even represented the esteemed businessman in one notable case valued at over $7,000. Thus, in the early 1900s, Law told Baldwin about his newest up and coming venture: Plasmon. On a trip to Europe, Law had met a man named Henry A. Butters, who was involved in several large enterprises throughout South Africa and California, and who had obtained in England the American rights to the patent for Plasmon. With Law’s milk (from his Briarcliff Farms) and money from geologist and gold mining engineer John Hayes Hammond, Butters believed that there existed potential for a great financial opportunity. The three men struck a deal.

Subsequently the first American Plasmon factory was built in Briarcliff Manor and began production. Woodward himself learned more of the whole ordeal when Butters sent to him an associate named Howard Wright. Baldwin and Wright initially became friends (although later Baldwin would come to believe that Wright was not altogether truthful). Wright asked the lawyer to organize the corporation that would take over and operate the Plasmon company. They set up a large office in New York City; Wright was named Manager and an Englishman named Ralph W. Ashcroft became Secretary. The company was incorporated in 1902 with a starting capital of $750,000. 4.

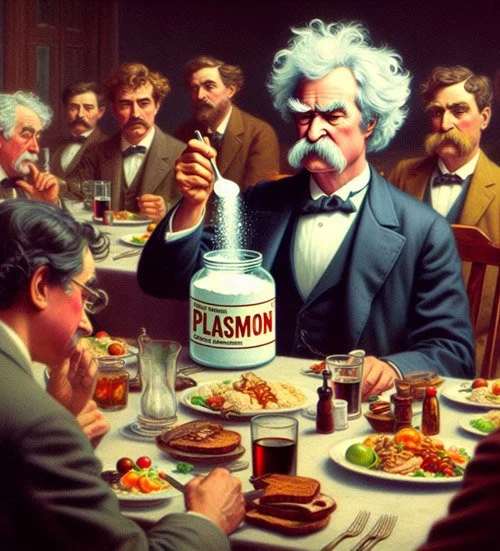

From its very beginning, the American Plasmon Company struggled. When Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) grew interested in the company—stating, “take plasmon into your stomach and trust in God”— he attempted to purchase through Butters a large portion of Plasmon stock taken from a pool of the founders’ shares. However, Butters, who recognized that the company might not perform as successfully as he initially believed, tricked the author, selling him $25,000 of his own stock. Butters vanished to California (or somewhere else; it’s not entirely clear where he went) soon after, sensing the anger of the others involved in the plasmon company. Wright disappeared as well, and Law— deciding he wanted nothing more to do with the business—also left the business.

This left primarily Ashcroft employed for the company. He expected a promotion to Manager. However, Hammond instead put Harry Wheeler, a relative of his wife in charge. Ashcroft, angered by the decision, formed a bond with Clemens over their shared outrage at how the company had treated them. Two dominant factions now existed: Hammond and Wheeler on one side, Clemens and Ashcroft on the other.

Some financial issues arose. Hammond formulated a plan: he’d run the business into bankruptcy and then buy the company out of its debt on September 24, 1904. This would essentially give him complete control over its assets. This led to a battle as Ashcroft tried to prevent Hammond and Wheeler from carrying out their strategy. At one point, Ashcroft even installed a dummy board of directors and attempted to lock Wheeler out of the building, all to prevent the latter from performing the steps necessary to declare bankruptcy.

Ultimately, however, Hammond prevailed, and the company declared bankruptcy. Ashcroft requested Woodward to serve as his attorney in recovering the Plasmon business. The case lasted for several months, during which Ashcroft sent increasingly unpleasant and aggressive letters to Hammond. He also published papers ridiculing him. When a commissioner finally ruled in favor of Ashcroft and Clemens, the scales seemed to even out. Supporters of both sides of the table were installed as new board members.

But the conflict had already paved the way for the company’s collapse. Clemens stated in the end that “the company failed because of bad management… Most of [my money] was lost through bad business. I was always bad in business.”

“Although it died slowly, Plasmon finally died. By December 11, 1909, while Clemens was in Bermuda: ‘The office has been discontinued, and all the bills of the Company have been paid through a prorate contribution of the shareholders, our friend Ashcroft to this end actually producing the sum of $90 in cash. Mr. Clemens’ prorated portion was $350, which sum was advanced by Mr. Loomis.’ The grand, decade long scheme was over, having cost Clemens at least $50,000 in losses and an unpardonable expense of time and energy” 5.

Although the Plasmon Company of America failed, Plasmon did find some success internationally. In 1902, physician and nutritionist Casare Scotti founded the Italian Plasmon Syndicate to research and sell pure plasmon specifically to infants. In 1916, the Syndicate changed its name to the Plasmon Company and did well throughout the course of WWI. Over the next few decades, its business expanded, and its production grew. In 1948, the company implemented its first automatic production scheme, allowing a single team of seven women to produce 5,500 boxes of Plasmon biscuits per day. 6, 7.

Interestingly, Plasmon biscuits are still sold worldwide by (as of July 2025) the NewPrinces Group in Italy. Although pure Plasmon no longer captivates the market, the Plasmon brand specializes in biscuits and other baby food and shows no signs of stopping soon. Specialty Italian food stores, alongside other larger retailers like Walmart, offer Plasmon biscuits in the United States, too. 8.

Plasmon Cookery Book

So the next time you find yourself curious for new food, buy a package of slightly sweet, crunchy Plasmon biscuits. And as you savor the crumbs, make sure to remember the incredible history connecting the business to Samuel Clemens, Walter Law, William Woodward Baldwin, and Briarcliff Manor. The Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society even has a Plasmon cookbook to help you along. You can probably substitute modern skimmed power for Plasmon.

Sources:

Public history student, “Fad or Food of the Future? Uncovering the History of Plasmon Protein Powder,” Public History Amsterdam, 09/28/2023,

Wikipedia - Plasmon Biscuit also Plasmon (dairy product)

Plasmon, biscuits for young and old, alike, Made in Italy,

Mark Twain Concern Gives Up the Ghost, NY Times, 12/21/1907.

William Woodward Baldwin 1862-1954: His Era Immensely Simplified. Collected and Compiled by His Granddaughter Patricia Woodward Baldwin Andrews. Baltimore, Maryland, 2012

Plasmon. Plasmon products on the Cento website.

Plasmon since 1912: 100 Years of History, On Plasmon Libya website.

Kraft Heinz Announces Agreement to Sell Italian Baby and Specialty Food Business to Italy’s NewPrinces Group. Announcement on the KraftHeinz Company website dated: Thursday, July 10, 2025.