Walter W. Law - From Rugs to Riches. Notebook 2025-7.

By Ian Cressman.

Walter Law’s letterhead showing the scope of his activities in the early 1900s along with his famout motto: “Briarcliff. Where only the best is good enough”.

At the age of 8 or 9, Walter Law heard a phrase from his father that would help define the remainder of his life: “If a Cobbler by trade, I’ll make it my pride to be the best of all Cobblers to be; and if only a Tinker, no Tinker on earth shall mend an old kettle like me.” Through each stage of his life—a young immigrant wandering New York City streets, a growing businessman in the carpet industry, a leading producer of high quality dairy products nationwide, the owner of one of the largest and most luxurious hotels in New York, and the founder of Briarcliff Manor—Law remained true to his father’s words. Over many decades, he would live by the idea that, as he later stated, “nothing is good enough if it can be bettered.” 1, 2.

Walter was born on November 13, 1837 in Kidderminster, England. At the time, the carpet industry was booming in Kidderminster; Walter’s own father, John Law, was employed as a yarn agent and then a carpet dealer during Walter’s childhood. The influence of the carpet business would become clear later in his life.

The Limes. Walter Law’s childhood home in Kidderminster, UK

Although Walter had nine siblings, he was clearly the favorite son of his mother, Elizabeth Bird Law. His parents sent him to work at a draper’s shop at the age of 14, likely to protect him from bad influences of the outside world. Their partiality toward him may have resulted from his intense devotion to their Nonconformist religious practices. During a speech for his 70th birthday, Walter remembered how his favorite childhood memories came from when his mother “took me by the hand and led me upstairs to the bedroom, and shutting the door would kneel down and pray there with me.” The Nonconformist nature of his household also directly informed his interests. Walter was a strong and passionate reader, and he took a specific interest in America, where all religious sects were protected by law. The idea that hard work, rather than class, became the foundation of success, had a strong appeal to the young Walter. 3, 4.

As he grew, Walter began to record words and phrases from his daily life in a small pocketbook which he carried around everywhere. One quote from the book read, “He is never alone who is accompanied by noble thoughts.” Indeed, Walter continued striving to keep his thoughts true to his hardworking, honest background. Perhaps this simple sentiment became the key to his ultimate success in America.

New York, 1860s

On January 23, 1860, Law arrived in New York. He had left his parents and family behind in Kidderminster, and although he travelled first class to the United States, he had in his pockets only enough money to last him about two weeks, in addition to some letters of recommendation from his father. 5.

Although in 1861, Law found some work for a carpet dealer for $1 per day, he resigned after realizing that the company engaged in false advertising and marketed domestic rugs as expensive, foreign products. The business fell soon after. Law began another job later in 1861, but that failed due to the start of the Civil War.

For a time, Law remained essentially jobless. He later referred to this period of his life as the “dark days.” And yet even here, he held tight to his religious beliefs and moral foundations, assured that he would carry on. When a member of the British Parliament with whom Law had previously connected sent the latter $50, Law directed it back to his parents, who he believed had greater need for it. For Law, those days “were the making of me. They were the developing of the man in me… What did God mean by sending me into this world? There was a place for me; I was in that place, and although it was dark around me I would not retrace my steps. I believed that there was light ahead…”

Sure enough, light soon came. In 1862, Law found a position at W. & J. Sloane, which had been founded as a carpet retail company about 20 years earlier. When Law entered the company, the business employed only four other salesmen; Law, still relatively inexperienced, seemed an unnecessary addition. Upon joining, Law recognized the immense generosity of his employer, William D. Sloane, and set out to learn everything possible about the industry.

One summer soon after his entrance into W. & J. Sloane, Law spent his two week-break testing whether wholesale selling would be a beneficial endeavor. He succeeded and quickly came to lead the development of W. & J. Sloane’s wholesale department, which proved even stronger than initially expected due to high demand from a nation engulfed by the Civil War. The department began with only a dozen looms and outputted only a few thousand dollars per year, yet by Law’s 70th birthday, those same statistics were 500 and several million, respectively. At the birthday celebration, Sloane recalled, “The energy of Law… did more to build up the wholesale business of the carpet industry in this country than the efforts of any other man living today.” Throughout the 1860’s, 70’s, and 80’s, the Sloane company expanded into selling furniture, furnishings, and antiques. Its headquarters moved to a high-status Fifth Avenue location in New York City, and Sloane himself worked with wealthy, elite clients. The Sloane company continued to grow well into the 20th century.

Just as Sloane’s impression of Law was strong, Law also had immense admiration for his employer. Near the beginning of Law’s employment, a friend told Sloane that he, the friend, would be entering the carpet business in Minneapolis, and that he’d pay a high rate for a young business partner. Yet even when Sloane recommended Law to take the position, Law refused, stating “I came in here when I was of no use to you in this business, and if I now know anything about it… I would rather you would have the benefit of it.” Law never regretted his decision. He later described the experience, example, and personality of Sloane as “the guiding ideal of my life… Pure, sweet, energetic, clear in judgement. It is his gentleness that, if there is any goodness in me, has made me great.”

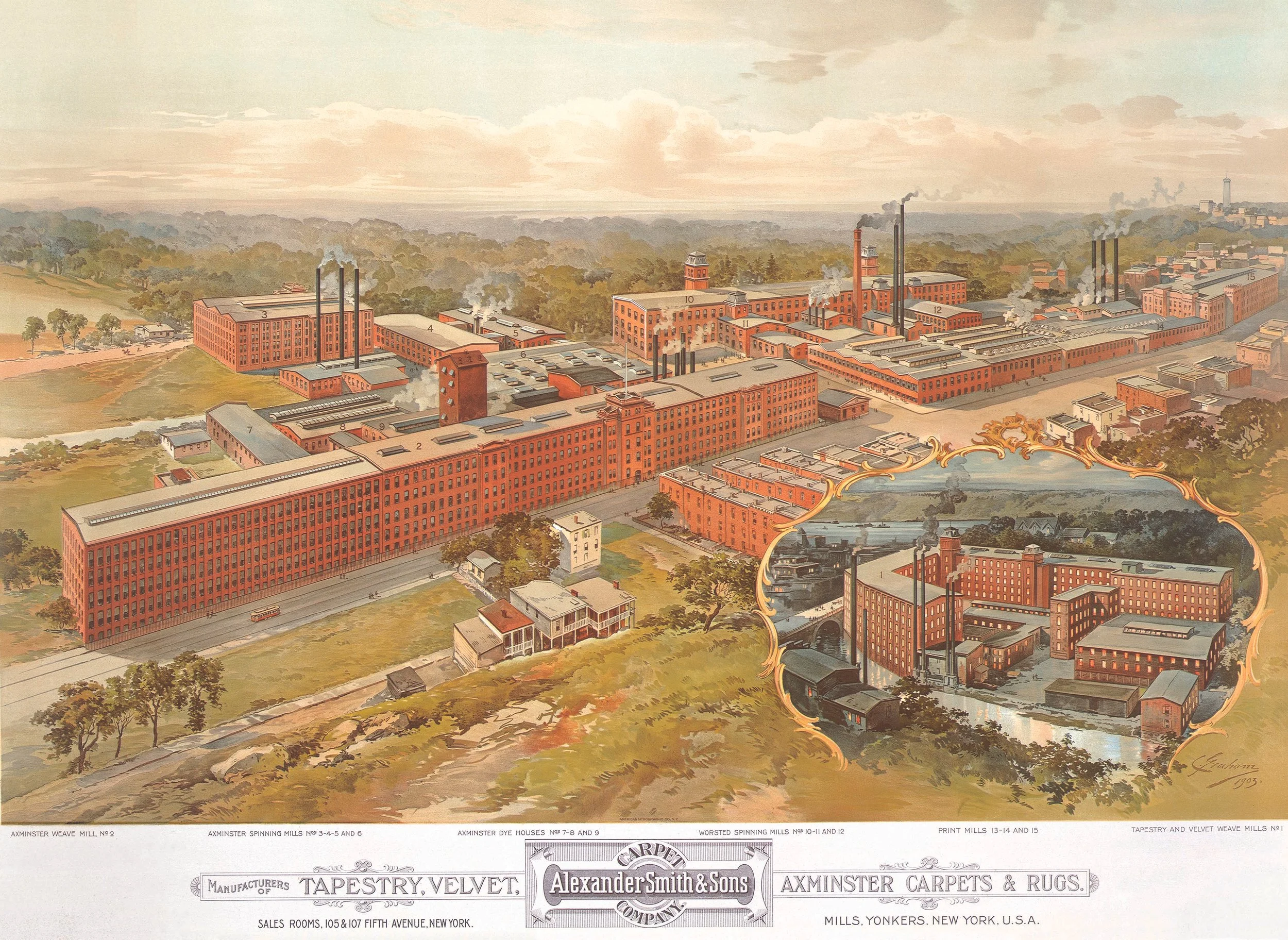

In 1873, when the selling agency of Alexander Smith & Sons Carpet Company was transferred to W. & J. Sloane, Law became the agency’s manager. An early stockholder in the Smith company, he moved his family—by now a wife, three sons, and four daughters—to Yonkers, New York, where the factory was located. Within just one year of the relocation, Alexander Smith’s son, Warren, reported that the factory made more profits than any other business in Yonkers. The carpet industry quickly became the city’s economic backbone, employing thousands of residents over the next few decades. Many workers referred to the company as “just like a family,” and although the factory relocated in 1954, an 87-year-old former employee later stated that, “I’d be working there yet, if the shop were there.” The mill also often employed residents who followed Law’s own, Calvinist ideas that success was hard-earned and a sign of God's graciousness. The Smith company eventually became a leading rug company internationally, with Walter Law sitting on its board. 6, 7.

Alexander Smith Carpet Mills, 1903

After successes with both W. & J. Sloane and Alexander Smith & Sons, Law retired in 1898. Yet retirement for the 61-year-old man didn’t entail an end to his endeavors. Rather, it meant the start of a new journey into animal husbandry, hotel management, and the eventual founding of the Village of Briarcliff Manor.

Law had already purchased 236 acres of Briarcliff Manor in 1890. The land was relatively cheap and possibly unsuitable for agriculture, but just as Law had dived into learning the carpet trade with swiftness and determination, so too did he now enter the world of farming. Over the next decade, Law rapidly bought land and bred cattle, so that by 1902, he had invested over $2.5 million (or approximately $60.5 million in modern USD) into his newfound “Briarcliff Farms.”

Briarcliff Farms. Pastoral Scene ca. 1900

Law set out to turn Briarcliff Farms into a pioneer of the production of clean, high-quality dairy products. At its peak, the farms contained over 2500 pure-bred Jersey cattle, approximately 500 workers, and about 5,000 acres of land. Noting Law’s ownership of vast property, Andrew Carnegie, jokingly referred to his friend as the “Laird of the Manor.”

Law enforced high standards upon his workers, and instructed them to treat the cows with the utmost care. One Briarcliff Farms booklet noted, “A Briarcliff Farms’ cow, by the time it has reached its third year, has received as much attention as an average human child of the same age.” Law was even known to fire any employee he saw kick a cow. The farm eventually produced approximately 3,000 to 4,000 quarts of milk per day, in addition to other dairy products like cream and butter. Law’s milk even won a gold medal at the 1900 Paris Exposition, the time’s equivalent of a world fair. 8, 9.

One of Walter Law’s prize bulls.

If Law ensured excellent treatment of his cattle, he also showed incredible generosity toward workers who followed his directions. He built small cottages for married employees, selling the living spaces on generous terms and holding the mortgages himself. For unmarried men, Law constructed a large, modern dormitory called “Dalmeny.” The walls of Dalmeny contained various mottos for the workers, including the phrase his father had told him as a boy of 8 or 9: “If a Cobbler by trade, I’ll make it my pride to be the best of all Cobblers to be; and if only a Tinker, no Tinker on earth shall mend an old kettle like me.” In 1896, Law funded the construction of the Briarcliff Congregational Church, specifically so his employees could attend church easily while living in Briarcliff. He also wasn’t immune to smaller, more fun favors; every Christmas, he distributed prizes for workers who best followed various standards, such as “neatest room” and “gentlest handler of cows.” 10.

Law’s generosity toward his workers also served another purpose. In 1899, he attempted to incorporate the area around Briarcliff Farms under the already-existing hamlet of Scarborough. This failed, however, so Law set his sights on an alternate route: founding an entirely new village himself. By 1901, with the help of his cottages to achieve the 28 persons per square mile and 25 adult freeholders necessary, Law was able to submit a petition to incorporate a new village. Thus, Briarcliff Manor was established on November 21, 1902.

With the founding of Briarcliff Manor, Law needed other developments to sustain the village and its population. Over the next decade, he expanded the church, built and expanded multiple schools, and funded large portions of equipment for the newly-created Briarcliff Manor Fire Department. He also began several other highly profitable endeavors, including greenhouses that grew Briarcliff and American roses, and the Briarcliff Water Company, which strove to produce pure water with no misleading advertisements. 11.

Briarcliff Table Water, 1414 Pleasantville Road.

Additionally, in 1902, coinciding with the founding of Briarcliff Manor, Law opened his grandest undertaking yet: the Briarcliff Lodge, a massive resort hotel overlooking the Hudson River. By 1909, when the North and West wings were added, the hotel consisted of 221 rooms and was situated on a property which was 184 acres in size, making it one of the largest resort hotels in the world. The rooms themselves were magnificent, and the hotel hosted countless weddings, receptions, and dances for the elite of the time. Food and drink at the Lodge were also sourced directly from the Briarcliff Farms, connecting Law’s multiple ventures in a series of elegant and efficient strings. Some of the hotel’s many luxuries included a small theater, a garage containing Fiat touring cars and limousines exclusively for guest use, an incredible garden and beautiful scenery, and a 9-hole golf course that eventually expanded to 18 holes in 1923. The lodge would eventually attract renowned guests including golf professional Gene Sarazen, Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Edison, and Babe Ruth. In 1906, Law even replaced the old Whitson’s Corner train station with a larger, more extravagant building that matched the Lodge’s Tudor Revival-style architecture. He believed that this would entice more wealthy guests to travel to Briarcliff. 12.

Briarclif Lodge

Up until his death in 1924, Law continued to spend his time and resources to develop the village. In 1901, Law founded the Briarcliff Realty Company, which proved pivotal in attracting permanent residents to the area. Between 1907 and 1908, Law used the Realty Company to help relocate his Briarcliff Farms up north to Pine Plains; crucially, this opened up land for more people to settle within Briarcliff Manor. By keeping road conditions immaculate, maintaining and expanding educational institutions, and even sponsoring a road race in 1908 that attracted 100,000 people, Law aimed to put Briarcliff on a steady path toward growth.

But despite Law’s many accomplishments in pioneering an internationally-renowned dairy company and founding and developing Briarcliff Manor, he remained the humble person of his past. When speaking at his 70th birthday party, he said, “I can talk about Briarcliff, for I love it with all my heart; I love every interest of Briarcliff… When it comes to talk about myself, that is a very different thing. I have told the reporter who came up here to see about Briarcliff: ‘here it is; you can see it; you can talk about it; you can take your pictures of it; only keep me out of it; I don’t like that part of it at all.” He further demonstrated his humility by refusing to put his name on any of the town’s physical locations; even the park, originally identified as Liberty Park, was only renamed to “Walter Law Memorial Park” in the 1950’s. 13.

Law also remained devoted to the religious beliefs and values that his parents had instilled within him as a child. He went to church twice per day without failure. Once, when the Premier of Canada grew interested in his farming methods and told Law he would visit Briarcliff the following Sunday at 11, Law replied, “I already have an engagement every Sunday at 11 a.m,” referring to his attendance at church. Just before the Old Meeting Congregational Church—the church in Kidderminster that Law had grown up attending—was demolished in the 1880s, Law bought wood panelling from the church to install back in his Briarcliff Manor home. In justifying the purchase, Law later referred to Richard Baxter, a famous 17th century Puritan minister who preached at the Old Meeting Congregational Church and was foundational in expanding the Nonconformist movement. Of Baxter, Law said, “there is a sacred memory even in the wood that he preached to.”

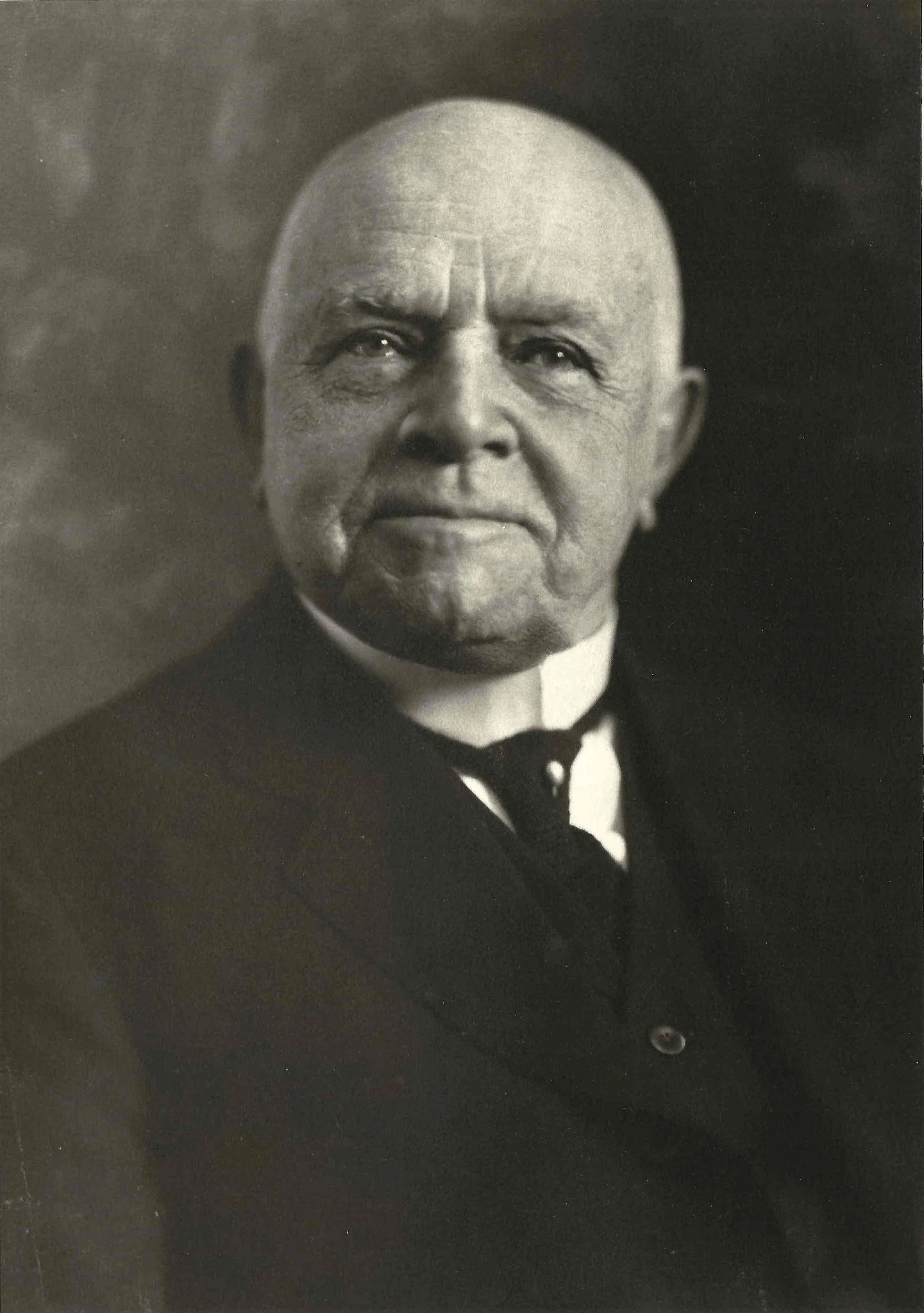

Walter Law in December 1923, one month before he passed away

Law died in Summerville, South Carolina, on January 17, 1924. Yet his faith in Briarcliff Manor extended far into the future: “I have a strong conviction that with the golden rule always in the ascendant Briarcliff Manor will go on to increase both in numbers and moral power, each member of it as one happy family, filled with charity and thoughtful consideration for his neighbor, and above all, having the blessing of the Lord.” Law believed that the future of Briarcliff—rather than himself—was the story which mattered. He had given a village not only its physical beginnings, but had imbued within it a sense of honesty and morality that he believed would lead to lasting success.

For Law, to become the greatest Tinkerer or Cobbler, as per his father’s motto, he had to leave something behind from which others could benefit. For what is a Tinkerer without the repairs he provides for the community? What is a Cobbler without the shoes he mends, which will carry customers far and wide? Indeed, Law’s favorite poem—“The Bridge Builder,” by Will Allen Dromgoole—reflects this idea that a legacy doesn’t center around remembering the individual who created it, but around its impacts in helping others.

“The Bridge Builder” is a simple poem about a man who, in his travels on a lone highway, stumbles upon a chasm in the road. He crosses it easily given his ample experience, but rather than continuing his journey, he builds a bridge spanning the gap. When a nearby pilgrim asks the man why he has built the bridge, despite having already crossed the chasm, the man responds:

“There followed after me to-day

A youth whose feet must pass this way.

This chasm that has been as naught to me

To that fair-haired youth may a pitfall be;

He, too, must cross in the twilight dim;

Good friend, I am building this bridge for him!’” 14.

Walter Law’s life encapsulates this ideal. After working hard and achieving success at an early age, his efforts to found Briarcliff and push its development in a constantly better direction ultimately paved the path for future hotel employees, farm workers, residents, firefighters, local politicians, and thousands upon thousands of families. While Law’s journey embodies a classic rags-to-riches story, it also highlights the importance of having a strong, determined, and honest character to create such a narrative. One can rest assured that even now, over a century after Law’s death, his father would look upon Briarcliff and beam with pride for his son.

Sources:

Rob Yasinsac, “Images of America,” (New York: Arcadia Publishing, 2004)

Bob Millward, “Walter William Law 1837–1924 ‘A Kidderminster Expatriate to New York,’” Kidderminster: Kidderminster & District Archaeological & Historical Society, 2018

Andrew Carnegie, “The Laird of Briarcliff,” 1908

An Address by Walter Law, delivered to Briarcliff on May 14, 1907

Edith Foldes, “Walter William Law’s Briarcliff Manor”

BSMHS Files

John Masefield, “In the Mill,” London: Heinemann, 1941

Briarcliff Farms Booklet

Mary Cheever, “The Changing Landscape: A History of Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough,” (West Kennebunk, ME: Phoenix Publishing, 1990)

Obituary from the New York Times, Walter W. Law, January 19, 1924

Robert Pattison, “A History of Briarcliff Manor,” Briarcliff: The Briarcliff Weekly, 1939

Wikipedia article: Briarcliff Lodge

Tien-Shun Lee, “Briarcliff Almanac: Law Memorial Park” Daily Voice, 5/26/11, https://dailyvoice.com/new-york/briarcliff/news/briarcliff-almanac-law-memorial-park/421497/

Will Allen Dromgoole, “The Bridge Builder,” EP Dutton & Company, 1931